Syndrome Description

Learn more about M-CM

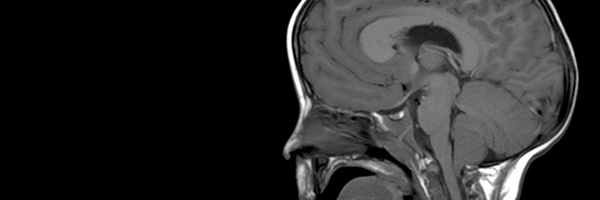

Brain overgrowth and abnormalities are a primary characteristic and cause of complications in M-CM. Abnormally large head size is called macrocephaly. The main cause for a large head in M-CM is megalencephaly, although an additional problem such as hydrocephalus can make the head even larger.

The human brain is a paired organ composed of two halves that look similar. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) typically fills the space within the lateral ventricles.

Ventriculomegaly, or enlarged lateral ventricles, is commonly seen in M-CM and is a term sometimes used interchangeably with hydrocephalus. Ventriculomegaly can be a result of the overall enlargement of the brain in M-CM. When the enlargement is due to poor circulation of cerebrospinal fluid, and CSF accumulates causing increased pressure in the brain, hydrocephalus is present.

Sometimes one side of the brain is larger than the other and malformed, a condition called hemimegalencephaly. If one side is larger but not malformed compared to the smaller side, this would be referred to as asymmetry. The terms hemimegalencephaly and brain asymmetry are often used interchangeably, but some feel this is not precise.

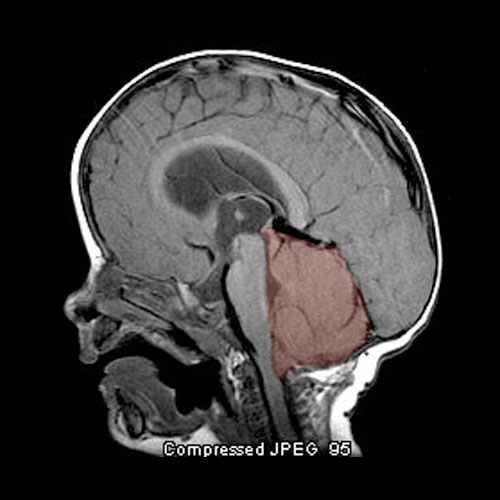

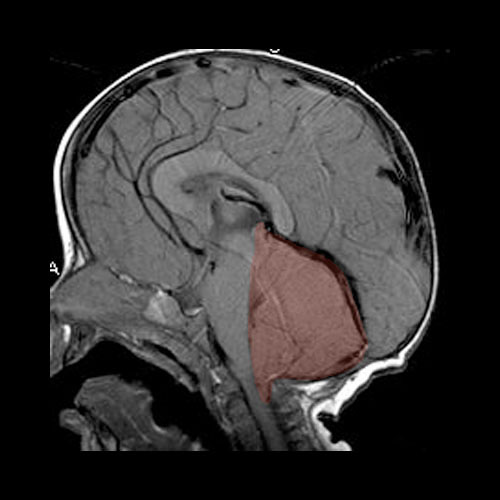

Another important neurological finding in M-CM is cerebellar tonsillar herniation (CTH, often referred to as Chiari). As with the rest of the brain, the cerebellum tends to grow disproportionately faster in children with M-CM. The rate of brain growth is too fast for the skull to keep up and reshape iteslf. The cerebellum rests in a cavity at the back of the skull called the posterior fossa. The posterior fossa is a restricted space surrounded by bone and a flap of fibrous tissue at the top. As the cerebellum grows, it fills this confined space. When the cerebellum gets too big, the cerebellar tonsils protrude and herniate down through the foramen magnum leading to CTH. Therefore, CTH is typically acquired over time in M-CM as the brain grows and is why it may not be present in a newborn or in early infancy.

Sometimes CTH is described as a Chiari I malformation on brain imaging studies such as CT or MRI. While both CTH and Chiari I malformations involve herniation of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum, not all cases of CTH are true Chiari I malformations. Classically, a Chiari I malformation is described on brain imaging as cerebellar tonsilar herniation of more than 5 millimeters below the foramen magnum. This definition, however, does not clarify the underlying cause. A Chiari I malformation is caused by a small or abnormally formed posterior fossa and therefore is a defect typically present from birth. A congenital Chiari I malformation can be an isolated finding in an otherwise normal individual but can also be associated with other conditions. An isolated Chiari I malformation can show no signs or symptoms and is often discovered incidentally when a brain CT or MRI is done for some other reason.

Cerebellar tonsilar herniation, regardless of the underlying cause, can lead to compression or pressure on the brainstem. The herniation can also cause reduced CSF flow through the foramen magnum leading to increased pressure within the brain. Not everyone will have symptoms, but important signs of brainstem compression include:

Infants may have difficulty swallowing, irritability when fed, excessive drooling, a weak cry, gagging or vomiting, arm weakness, stiff neck, breathing problems and developmental delays. If a child has any of these or other concerning symptoms, it is important to seek medical care right away. If the signs are not recognized early and treated immediately, children can suffer severe complications including sudden death.

Other common neurological findings in M-CM include:

Most children with M-CM have hypotonia. Hypotonia can be caused by problems within the brain or muscle and is seen as part of many different conditions that affect muscle control. Hypotonia in M-CM is thought to be due to problems within the brain and is another factor that contributes to developmental delay in affected children. The hypotonia in M-CM often improves with age, however, underlying neurological problems can cause this to be an ongoing issue even in older children.

Order brochures or download a PDF

Guidelines from published research literature

Guidance for clinical genetic testing

Explore the results of a patient survey conducted in 2012

Explore the research literature related to M-CM

An extensive list of resources